I recently had the great pleasure of being a guest on the podcast, ParaGhoul Paranormal: Discoveries from the Dark, hosted by Keely Kulpa. (You can listen to it here or watch it here.) On the episode, I told the story of the murder of Scotty McLachlan at Beechy, SK. I’ve told this story on my website before (here), but over the past year I’ve done a deep dive on the case. I was lucky enough to receive police reports and transcripts of the preliminary hearing from the provincial archives, as well as the Coroner’s Inquest report, all of which revealed more details about the crime and the people involved.

I’ve rewritten the story of the McLachlan murder, but be forewarned: this is a long one! So, without further ado, I give you:

The Mind Reader and The Murderer

On the evening of December 10, 1930, the residents of Beechy were excited, despite the freezing cold.

Performing at the hall was ‘Professor’ Henry Gladstone, a self-described mind reader and water diviner. A former Vaudevillian who’d gone by the stage name ‘Professor Mem-O-Rea, the Mental Marvel’, Gladstone was tall with a pointed gaze and a striking level of self confidence.

The story he told reporters was that he was born late in the night, with a caul over his face, in Lancashire, England in 1888. He proudly stated that he was the seventh son of a seventh son and a direct descendant of former British Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone. Unlikely, as the man’s seventh child had no children. There was also certainly no proof he’d attained any academic credentials worthy of the title ‘Professor’. Either way, Gladstone’s well-cultivated mystique seemed to be working for him as he entertained his audience in Beechy. As part of his act, he invited members of the audience to put questions to him mentally, which he answered without them having to utter a word.

It was during this portion of the show that Gladstone pointed at a member of the audience, a man named William Taylor.

“The man you are thinking of was murdered. There was foul play and the body will soon be found.”

Murmurs and whispers filled the hall as William Taylor admitted he’d been thinking about James S. McLachlan, or Scotty, as he was known in the district. Scotty had disappeared in January of 1928, supposedly leaving for British Columbia, but no one had heard from him since and he’d left horses, equipment and belongings behind.

Also in the audience was Constable Charles E. Carey of the RCMP. He’d been in charge of the Beechy detachment for the past four and a half years and had been investigating the disappearance of Scotty McLachlan since December of 1928. At Professor Gladstone’s pronouncement, he felt a small spike of excitement. He’d never given up on the case. In fact, he’d just reached out in October to Detective Sergeant C. C. Brown in Saskatoon for assistance. He felt sure that if another investigator questioned people in the district, someone would let slip some small detail that would help break the case.

Gladstone pointed at Carey, where he sat with Constable Kelly. “And you’ll be with me when I find the body.”

The hall filled with the dull roar of whispered exclamations. Rumors and gossip were sure to flood the community after Gladstone’s assertions, and Carey realized he had a golden opportunity. All that talk was bound to make someone nervous. The time was ripe to make further efforts to clear up the McLachlan matter. He just needed a little help.

On December 12th, he once again reached out to Detective Sergeant Brown and this time he was successful. Brown informed him that Detective Corporal William John Woods was en route to Beechy to assist him.

Woods arrived in Lucky Lake that evening and Carey was there to greet him. He told him about Gladstone’s pronouncement at his show and pointed out that he was giving a performance at the local hall in Lucky Lake that night. They may as well go to the show and interview him afterwards.

After some discussion, they agreed they had nothing to lose and potentially everything to gain in asking Gladstone to accompany them through the district as they re-interviewed the various locals connected to the case. Whether his gift was real or not, perhaps his presence would result in a lead.

Gladstone was only too glad to have the chance to assist the police. After all, it wasn’t his first time helping authorities locate a body. He claimed to have found 120 bodies lost to water in Canada, one such body being that of Alexander McDonald in Alberta’s Red Deer River in 1924. The old miner had been missing for six months and Gladstone correctly predicted where they’d find his remains, in a swirling eddy downriver from a railway bridge. His methodology included bread and limestone. He would stick a piece of limestone in bread and drop it into the water, following it along the current until it stopped or swirled in a specific spot.

It was more of a neat bit of science than psychic ability, but either way it seemed to work.

Gladstone was quite confident that McLachlan’s body would be found on his old farm. He told Carey and Woods that he would very much like to go to the farm and walk around to see if he could get a hunch or a feeling.

Scotty’s farm had been rented to him by a man named Olaf Evjin. It had originally belonged to Scotty, but he’d lost it through a tax sale. Evjin had bought it from the municipality in 1926 and let Scotty rent it with the intention of selling it back to him. In 1927, Scotty took on a partner named John Schumacher, who lived on the farm with him and still farmed there.

Scotty didn’t have much in the way of family. He’d come to the district in 1914. Six years later his wife died and his two kids became wards of a family named Moore in the Herbert district. He had a sister, Mary Heron, in Vancouver, but that was it. At the time of his disappearance he was in his mid to late 40s.

The group decided to go out the following morning, on December 13th, to begin their interviews. The plan was for Woods to do most of the questioning while Gladstone stayed in the background, ready to give them the benefit of any thought impressions he might get as a result of the answers given.

Their first stop was at the farm of Sam Berton in the Coteau Plains district. He was away. Next, they drove to the home of Oscar Lindman, a good friend of Scotty’s, but he was away as well. Undeterred, they went to see Earnest Hagemeister at his place.

Carey had been informed by Oscar Lindman and Abe Penner in previous interviews that Hagemeister had heard John Schumacher utter threats against Scotty McLachlan. Hagemeister always denied this, but Carey suspected there might be some truth in the claim.

For about 15 minutes, maybe more, Woods closely questioned Hagemeister about the alleged remarks Schumacher made against Scotty. Hagemeister flatly denied any memory of telling anyone such a thing. Woods told him Penner was ready to swear to it, but Hagemeister was unmoved.

Gladstone suddenly interrupted the interrogation, looking directly at Hagemeister and saying, “I’ll tell you exactly what his words were on that occasion. He said, ‘I’ll kill that Scotch bitch before he leaves the place.’”

Further, he informed Hagemeister that he was sick in bed with pneumonia at the time.

After hedging for a minute or two, Hagemeister finally admitted that Gladstone was right. Schumacher had said something to that effect and he had been sick in bed at the time. He didn’t have pneumonia, but a bad chest cold and had been worried it was pneumonia.

Carey and Woods were quite startled by this demonstration of Gladstone’s ability. Feeling more confident in their decision to include him, they continued onward with a few more interviews before arriving at what was now known as the Schumacher farm.

They left Carey, who was in uniform, in a quiet spot on one of the side roads and Woods and Gladstone drove on to the farm. They were posing as two water diviners in case Schumacher happened to be home. They weren’t ready to question him yet and didn’t want to spook him.

They went to the house and asked for one of the neighbours, pretending to be on the wrong farm. Schumacher and his wife were away, so they were greeted by a hired hand, Schumacher’s young brother-in-law. Woods explained that they were looking for water, that Gladstone was a water diviner and would be able to find it, if they could have a walk around the property.

When the hired hand gave them the go ahead, they began to explore the yard. Gladstone led them over to the barn, then away, before returning to the barn again. In several spots Woods had to take Gladstone’s arm, as he was partially blind.

On their third and final return to the barn, Gladstone began sniffing the air loudly, telling Woods he could smell something. Woods told him he was crazy. He couldn’t smell anything. “I have as good a smeller as you have.”

“There’s something funny here,” Gladstone responded. Before he could say anything else, the hired hand joined them and they ceased conversation.

Gladstone led them down to the well below the barn, still acting strange and preoccupied, murmuring that there must be another well that wasn’t being used or something.

From there they walked to the house and warmed themselves at the stove, chatting with the young man before telling him they’d be back later in the day.

As soon as they left the farm and returned to Carey, Gladstone shared his impressions.

“There has been trouble there for Scotty. McLachlan has been killed at the barn and is buried nearby.”

He was emphatic that McLachlan was killed in the barn or else buried under the floor in the barn. He claimed something told him that the old well had some connection with the murder as well. Despite Woods and Carey’s fear that the body had been burned, he was adamant that the body was buried on the land and that the barn figured into it in some way.

At about 4:00 p.m. they returned to Beechy to interview Abe and Pete Penner before returning to the Schumacher farm. When they went back, John Schumacher was still not home. It was dark as they drove back to Beechy, but about three or four miles outside of town, they met an old Ford truck on the road, driving without any lights.

Carey immediately had a gut feeling that Schumacher would be in that truck and turned the car around, catching up to it and pulling it over.

Woods got out of the car and went over, asking if one of the men inside was John Schumacher. When the passenger identified himself as such, Woods called him out of the truck and asked if he would have any objections to returning to Beechy with them.

He told Schumacher he’d been brought in to assist in making a very thorough investigation into the disappearance of McLachlan, and naturally, he was forced to start with John as he was the last person to see him alive. He told him that they’d already been to his farm twice and been looking over the place very carefully.

As Woods gave his explanation, Schumacher grew visibly nervous. He agreed very willingly to accompany them back to Beechy, once they’d settled on how he’d return home when they were finished, but the whole time his speech was halting, his nervousness palpable.

Now, Constable Carey had obviously interviewed Schumacher multiple times since Scotty’s disappearance. The first interview was on December 8, 1928. At the time he received no hesitation from Schumacher, who told him about renting a half section of land from McLachlan in the spring of 1927. He’d lived on the farm with Scotty until about February of 1928 when Scotty left. He told Carey that Scotty left in the morning, dressed in his work clothes, a combination of blue overalls, heavy stockings, ordinary light rubbers and a sheep-lined Mackinaw. Scotty hadn’t told him where he was going, but all winter he’d been talking about going to B.C., so he assumed that’s where he went. He’d left a fairly good grey suit and some old clothes behind, taking a blue suit and a few other things with him in a sack.

He told Carey about how McLachlan had lost his lease to the farm. His landlord, Olaf Evjin hadn’t been happy with how little Scotty was getting out of the land and had approached Schumacher to let him know that he would be terminating Scotty’s lease and he could have it instead if he wanted, about two weeks before Scotty left. He’d bought all the equipment from Scotty, giving him $150 in cash and a promissory note for another $200 to be paid at the end of the season.

He hadn’t heard from Scotty since he left and had no idea where he was.

Carey interviewed him again on February 4, 1929, mostly about the various rumors circulating through the community. People were suspicious. Schumacher had traded a cow that was apparently Scotty’s to an E. Westlund in the district, as well as sold a few of Scotty’s horses. Schumacher told Carey he’d bought the cow and a heifer from Scotty in the summer of 1927 for forty dollars cash. The horses, he said, were his. As for the household goods? He bought them from Scotty before he left.

He couldn’t help it if people liked to talk, he told Carey. And that was that. There was no reason to hold him, no evidence that spoke to murder.

John Schumacher joined them in their car and Carey drove to the detachment office in Beechy. They went into the office and sat around the table, Gladstone taking a spot in the corner.

Woods took charge of the interview. He told Schumacher that they could produce a man who would swear that he’d made a threat to kill Scotty. He pointed out that Schumacher had sold property belonging to Scotty, and that they had a witness who’d seen him burn a set of Scotty’s false teeth. All true.

Schumacher gave only vague answers. He maintained his story that Scotty had left and he had no idea where he’d gone.

This went on for about ten to fifteen minutes, with Gladstone occasionally interjecting with a question of his own. It was beginning to feel as though the interview was going nowhere, when Gladstone stood up and snapped his fingers.

“The barn, yes, I’ve got it.” He turned to Carey and Woods. “Now, gentlemen, I am going to tell you just what took place out there. Scotty went to the barn, all right. There was a blow struck. Scotty fell down, he was murdered. The body was buried. It is still there, someplace near an old well.”

No one said anything. The room was silent for a minute or two, then Carey spoke up. “Well, John, you understand we cannot force you to tell us anything unless you want to, but if you desire to tell us–” he got up and retrieved a sheet of paper and pencil and laid them on the desk. “If you want to tell us about this, there is a paper and there is a pencil.”

Nothing more was said for another minute, the silence growing as Schumacher sat with his head down, his eyes on the floor. He began sniffling, then broke down and started sobbing.

“Oh my wife and my baby! Will they hang me?”

Woods shook his head. “I can’t say. I don’t know the facts of the case. If you want to tell us, of your own free will, I could better tell then.”

He cried for a few more minutes, nothing more being said, until Woods asked, “well, what about it, John? Do you want to tell us something?”

Schumacher nodded through his sobs. “Oh! I’ll tell you everything.”

Gladstone moved to the door.

“Well, gentlemen, I have to go or I’ll be late.” Nodding at Woods, he exited the room.

Woods placed John Schumacher under arrest, telling him he was charged with murder and gave him the full warning. He told him he could write down his statement on the paper.

“I can’t write very good. Can I tell you and you write it for me?”

Woods nodded. “Can you write your name?”

“Yes.”

At this point, Carey needed to leave to drive Gladstone back to Lucky Lake for that evening’s performance. Woods sat down next to Schumacher and after warning him again that he was under no pressure to tell them anything, nodded at him to go ahead and give his story.

This is the statement John Schumacher gave:

I cannot write myself, so I am asking Corporal Woods to write this down for me. I knew James S. McLachlan and we were living together on Olaf Evjin’s farm during the winter of 1927-28. I had a quarrel with him in the summer of 1927 over store bills. He tried to run up on me without my permission. We didn’t come to blows that time but he threatened to hit me with the frying pan. Olaf Evjin told me during the winter that he was going to rent the place to me. McLachlan would have nothing more to do with it. When McLachlan heard about this he accused me of getting him put off the place and finally sold me his stock and said he was going to leave. I paid him $150.00 cash and gave him a note for the balance which was over $200.

One morning, sometime in January, 1928, Scotty McLachlan came home. I think I was eating breakfast when he came in and said he was leaving. I went out to the barn and left him in the house and a little while afterwards he came out to the barn and started to quarrel with me. I don’t remember what words were said but he finally called me a bastard and grabbed a scoop shovel and made a rush at me. I was cleaning manure out with a four-prong pitchfork at the time and when he swung the shovel at me with the intention of killing me in the head, I swung the pitchfork and hit him over the side of the head once. He fell down and stayed there. I was scared and ran to the house, but I didn’t stay there a minute but ran right back to the barn. McLachlan was still laying there. I shook him but he didn’t wake up. I was so scared I didn’t know what to do and as I had no witnesses to the quarrel, I was afraid to tell the police and finally decided to bury the body. I left it for an hour or so in the barn and then dragged it out by one hand, I think to a manure pile below the well and covered it up with manure. I never searched the clothes on the body at all before putting it in the manure pile and did not touch it anymore than I could help. I didn’t feel for his heartbeat or anything like that as I was in a panic and didn’t know what to do. I haven’t put any more manure on this pile since or touched it in anyway but as far as I know the body must be still there. I am willing to go out tomorrow and show the police where I put it. I don’t think I have the pitchfork I killed McLachlan with, as I think I lost it off a load of hay last summer. I had no intention of killing McLachlan when I hit him with the pitchfork as I was only defending myself and I knew he would hit me with the shovel if I didn’t stop him. This is the whole true story of the reason for Scotty McLachlan’s disappearance and I am telling it of my own free will and desire to clear the matter up.”

Signed, John Frank Schumacher.

Carey returned from Lucky Lake at about 9:00 p.m. that night, and found Woods and Schumacher in the office, talking. Schumacher had finished giving his statement and Carey read it over. He started to read it aloud to Schumacher, but he shook his head.

“Corporal Woods read it over a couple of times to me.”

“Is all this true, John?”

“Yes.”

Carey nodded. “And is that your signature?”

“Yes.”

Woods and Carey took Schumacher to a cell. That night he slept like a baby.

The next morning, Sunday, December 14, 1930, Woods, Carey, Schumacher and a guard named Harry Payne they’d hired to watch over him, got into the police car and drove out to the farm.

As the car pulled to a stop east of the barn, Woods glanced at Schumacher.

“Where abouts is this pile, John?”

He pointed at what looked like a heap of snow. “It’s under there.”

“There’s a manure pile under that?”

“Yes, it’s under all that I buried him.”

They took Schumacher to the house and left him under the care of Harry Payne, the two handcuffed together. Woods and Carey went down to join the troop of volunteer diggers. Most of the community had turned up to watch the excavation, including Henry Gladstone. Among the diggers were Oscar Lindman, Sam Welch, Pete Roos and Al Weston.

The manure pit was east and a little bit south of the barn. Before the digging could begin they had to get through an estimated foot and a half of ice and snow. They dug with picks and shovels for about forty-five minutes, chipping away at the frozen manure with no luck as the crowds of people huddled against the cold, watching. With no sign of the body, Woods trudged back up to the house to see if he could convince Schumacher to come down and give them more direction.

But Schumacher didn’t want to go down and face the crowd. He looked at Woods and shook his head. “Please spare me that.”

“All right, John. We will try and find it without you if you don’t want to go down there.”

It was around this point that a man came into the house, agitated and upset, coming to stand in the doorway of the bedroom, where Woods was standing in front of Payne and Schumacher, who were sitting on the bed.

“What do you want?” Woods asked.

“I want to find out all about this.”

Woods looked him up and down. “Who are you?”

“I am his brother-in-law.”

“You better ask him, then.” Woods motioned at Schumacher and went out of the room.

Schumacher’s brother-in-law, Ivald Westlund, stepped inside the bedroom and sat down on a trunk across from the bed. “John, is this all straight goods? Is it true you did this?”

Schumacher sat with his head down, his gaze focused on the floor. After a moment he slowly lifted his head and said, “I guess it is.”

Ivald was silent. He sat on the trunk, obviously quite upset, and stared at the window for a while. Finally, he looked at Schumacher.

“My God, man. How could you carry on here?”

John Schumacher looked up at the ceiling, the silence lengthening. “Well, it has been pretty hard.”

Meanwhile, the digging was still progressing, but with no results. After another twenty minutes, Woods again returned to the house and asked Schumacher to come down.

This time he relented and Woods brought him to the dig site.

“You are in the right spot. The manure pile is not very big. He’s there, you’ll get him if you dig long enough.”

The manure pile was indeed not very big, only about ten feet by ten feet. And it was not long after Schumacher was brought down to verify the location that a piece of sock showed through the manure.

The digging operation slowed down considerably as they very carefully began chipping and scraping away at the manure with their hands so as not to damage the remains. Carey was especially anxious that no injury should be done to the head.

The feet were uncovered first, then slowly the rest of the body began to come into view.

“Yes, we’ve got Scotty,” Oscar Lindman murmured. “Looks like his clothes, anyway.”

They chipped around a fair-sized piece of frozen manure at the top of the body, making sure to stay far enough back from the skull that no damage should be done. As they gently lifted the manure, it released and the skull came up with it, so embedded in the frozen manure that it separated from the body.

Informed of the discovery, Schumacher asked Carey if they’d found anything else.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I mean the one hundred and fifty dollars.”

There was no sign of it. If it had been there at all, it had most likely disintegrated.

When the remains were fully exposed, it was between 11:00 and 11:30 a.m.. The Coroner, Dr. G. G. Leckie of Lucky Lake, was called and jurors summoned to view the remains.

The body was badly decomposed, with not much flesh left outside of a skeleton and clothes. It was lying on its back, with the left arm down at its side and the right arm lying across the chest.

All the woolen clothes were in a good state of preservation, but all the cotton portions, including seams, had completely disintegrated.

The body was very carefully lifted onto an old door and loaded onto a truck. It was brought into Beechy by Sam Welch, accompanied by Mr. Morgan and Pete Bradick. They took it to a building that stood on the corner in the north end of the village that used to be an old Red and White store with a butcher shop attached.

Constable Carey was waiting for them and took custody of the body. Harry Payne was once again employed as a guard, this time over the remains, until Dr. Walker Stewart Lindsay, a physician, surgeon and professor of pathology at the University of Saskatchewan, arrived to conduct the post mortem examination.

Dr. Lindsay was a serious looking man with glasses and a moustache. He’d joined the University of Saskatchewan in 1919 and for the next three decades played a pivotal role in the education of the province’s doctors. To say he was held in high respect would be an understatement. He created the Department of Bacteriology at the invitation of Walter C. Murray, the president of the University. His laboratory, housed in one of the greenhouses, was the first medical teaching facility in what would become the School of Medical Sciences in 1926. That same year he became the dean of Medicine and regularly conducted post mortem examinations in criminal cases.

He conducted the post mortem examination on the body believed to be Scotty McLachlan on December 17, 1930 at about 5:00 p.m.

In his testimony at the inquest he described the body as male, approximately 5’5” tall and completely covered in manure. It was dressed in a waist-coat-khaki shirt with two breast pockets and shoulder straps, laced mackinaw trousers coming halfway between the knee and ankle with patches on the seat and knees, four pairs of woolen socks and ribbed underwear with long arms and legs. The remains of two lined leather mittens were lying on the body.

In the right side pocket of the pants he found a watch, fob and chain. Also on the body were rusted wire armlets on each arm, braces with rusted catches and a short blue pencil with rubber attached.

As for the body, the left hand was missing with the left arm extended close to its side. The right arm was bent, the hand completely separated, its bones found embedded in manure on the front of the abdomen.

The head and three vertebrae were separated from the trunk and one cervical vertebrae was missing. There was some hair on the head that was fairly well preserved, although soiled from the manure. Dr. Lindsay guessed brownish as the colour.

The body was in a state of advanced decomposition, with the disappearance of nearly all soft parts except for the brain, some flesh at the back of the abdomen and some of the muscles of the back, buttocks, thighs and legs close to the bones.

He noted that there were only three teeth in the upper jaw with seven teeth in the lower jaw and that the sockets of the other teeth were closed, having been lost a long time ago. He found evidence of arthritis at the lower ends of both femurs and calcification of costal cartilages, meaning the body most likely belonged to someone over the age of thirty, who used dentures.

As to cause of death, Dr. Lindsay found evidence of an extremely heavy blow to the left side of the head (it had nearly driven in almost the whole of the left side), as well as what looked like evidence of a blow on the right forehead. In addition to these injuries, there was a fracture to the neck of the first rib on the victim’s left side. When asked how long the victim had been dead, Dr. Lindsay replied, “a very long time. A question of years rather than months.”

Oscar Lindman was the second witness at the inquest. He was not the talkative sort. He kept his answers short, never keen to elaborate or explain. He testified that he’d known McLachlan for about 14 years. His home was only two miles from Scotty’s and they’d visited each other often.

The last time he saw Scotty was at his own house, when Scotty came over for a visit. It was on a Saturday in January of 1928. He’d come over some time Saturday afternoon, stayed the night, and walked home the following evening at around eight o’clock. Oscar never saw him alive again.

When he left, he was wearing a pair of heavy breeches, a heavy Mackinaw smock, stockings and a pair of small rubbers, no shoes just rubbers, and a fur hat.

The following Wednesday, Schumacher had come over and told him Scotty had left; that he took a flour sack on his back with some old shoes in it, saying he’d come in broke and went out broke.

The next time Oscar saw Scotty was when he helped dig him up. He could only identify him by the pants he had on, laced up with his stockings pulled over the cuffs like he used to wear them. No one else in the district wore pants like that. He confirmed that Scotty carried a watch and fob, gold plated.

When asked about Scotty’s temperament, he stated, “he got a good disposition” although he admitted that he could be quarrelsome if he had a drink.

Sam Welch testified next, describing his role in bringing the body from the farm. He confirmed that Scotty wore dentures, a partial plate in his upper mouth. He said that Scotty had a good heart, but was quick tempered and quarrelsome when he had a drink in him. At other times though, he was very sociable.

Olaf Evjen was called. He confirmed that he’d decided to terminate McLachlan’s lease and give it to Schumacher. He wasn’t getting anything out of the land while Scotty was on it and he was dissatisfied. In the fall before Scotty disappeared he’d approached Schumacher in Beechy and told him he’d rent it to him.

Other witnesses included Jack Shultz, who’d witnessed Schumacher burning Scotty’s false teeth, Earnest Hagemeister, Constable Carey and Pete Penner. Pete had stayed with Scotty and Schumacher for about a week in January of 1928, before Scotty disappeared. He’d seen Scotty leave to go visit Oscar Lindman before he’d gone home. That was the last time he remembered seeing him. The following summer, Schumacher had mentioned that Scotty had taken a pack on his back with a few clothes and left.

During his visit, he noticed that Scotty and Schumacher were not getting along very well. Both would talk to him about the other and they’d argue sometimes, although he couldn’t remember what about. Scotty had shown him a grey suit while he was there that he’d sent to a man named Arthur Rose to get cleaned. He was very pleased with how it had come out. After Scotty disappeared, Pete saw the same suit on John McInnes, who said that Schumacher had lent it to him to wear to the stampede.

Abe Penner also testified about buying one of Scotty’s horses from Schumacher the spring after Scotty disappeared. Schumacher had told him he had permission from Scotty to sell it. Corp Woods also testified, followed by Harry Payne.

The final witness at the inquest was Richard Doak, who’d lived in the Beechy district from 1912-1918 before moving to Herbert. He was good friends with Scotty. Years ago, he’d given Scotty a gold plated, open faced watch. He’d bought two from a friend who needed money and gave one of them to Scotty.

Also asked about Scotty’s disposition, he said Scotty was easy to get along with and that he never had any trouble, although he could argue a lot and sometimes swore.

“He was always very nice with me.”

At the conclusion of the inquest, the jury reached a verdict.

“We are satisfied the body is that of James Stewart McLachlan and that he met his death about the month of January 1928 at the south-east quarter of section 3, township 23, range 13, west of the 3rd meridian, death being caused by a blow or blows inflicted on his head by a weapon in the hands of John F. Schumacher.”

With the body found at the farm now officially recognized as that of Scotty McLachlan, it was time to pursue the murder charge against John Schumacher.

The preliminary hearing was held in Beechy on Monday, December 29th and Tuesday, December 30, 1930 before Provincial Police Magistrate J. T. Leger. Representing the Crown was G. W. Murray Esq. and for the defense was D. Disberry Esq.

Dr. Lindsay submitted a supplementary report to go with his testimony at the inquest for the preliminary, stating that the injuries to the head and neck were the result of extreme violence, probably in the nature of one or more severe blows to the left side of the head and would be sufficient to account for death. He also pointed out that due to the advanced state of decomposition, the soft parts of the body had almost completely disappeared, making it impossible to say whether or not any organic disease existed.

The same people who testified in the inquest were witnesses at the hearing, with the addition of a few others, including Hannah Lindman, Oscar Lindman’s wife.

John Schumacher was committed to stand trial at the next court of competent jurisdiction, to be held at Kindersley in the spring.

Notably, Henry Gladstone was not one of the witnesses at the hearing or the inquest, despite the public’s desperate curiosity to hear from the infamous mind reader. He was suffering from poor health at the time. In fact, Gladstone’s health diminished to such an extent that he was hospitalized, confined to St. Paul’s hospital in Saskatoon for several weeks. He’d only been home for a few days when on February 2, 1931, his apartment building was ravaged by fire. Gladstone was ill in bed at the time, too weak to walk, and was carried from the burning building to safety by a firefighter and police officer while his wife and two young children waited outside.

The couple lost $10,000 in possessions to the blaze, including an ermine trimmed coat, ten diamond rings, a large ornamental beetle heavily studded with rubies that was apparently obtained in Turkey, and all the valuable records and photographs they had in connection with both his wife’s and his theatrical work (she was a professional dancer).

They had no insurance. Which might explain why Gladstone was in the news soon after in Edmonton on February 18, 1931, reportedly to consult on a criminal case that was baffling police. Of course, he wasn’t so busy that he couldn’t give interviews, or set up a few performances at the Rialto.

During one such interview, he declared that while in town he would solve “the foot mystery”, in which a black retriever named Gyp had brought home a human foot to its owner and officials had yet to find the rest of the body. A medical examination had come to the conclusion that the foot wasn’t treated with any embalming fluid or preservative, and while the owner reported that the dog generally wandered around within a block of the house, no one could find any trace of the remains. When asked where the rest of the body was, Gladstone pondered for a moment.

“It’s in the water somewhere. I’ll find it for you.”

Alas, he did not. But he did sell quite a few tickets to his performances.

John Schumacher was brought to Kindersley on Sunday, March 22, 1931 for his trial, which was scheduled to start on March 24th. He was permitted a visit with his wife and baby on the Monday, the day before his trial.

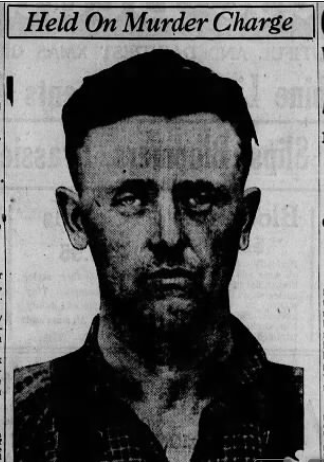

On the morning of the 24th, he entered the cramped, overcrowded courtroom with no display of emotion. He was an imposing figure at 6’4” tall and weighing over 200 pounds. According to his wedding certificate, he was 23. He told reporters that he’d not slept well and complained of a headache.

Before court convened, his wife arrived escorted by John’s brother, Leslie, who carried the baby, wrapped in a pink woolen blanket. She was given a seat in the room and took over the baby, while Leslie found a seat elsewhere in what journalists described as the small, inadequate courtroom.

The trial began at 10:00 a.m. sharp and was presided over by Justice John Fletcher Leopold Embury.

Justice Embury was an imposing man. He’d completed his law degree in Ontario in 1902, after which he immediately moved to Regina and established a thriving practice. He served in World War I, returning from overseas in 1918, where he was appointed a judge of the Saskatchewan Court of King’s Bench. When Schumacher’s trial opened he was 55.

Representing the crown was William Milverton Rose K.C. of Moose Jaw, assisted by George Murray, recently appointed crown attorney for the Kindersley judicial district.

Alfred Edward Bence K.C. acted alone as the defense.

The clerk read the indictment and in a low, clear voice John Schumacher answered, “not guilty.”

William Rose had an interesting job as the prosecutor. It was already established that John Schumacher had killed Scotty McLachlan; he’d confessed to it. The real question before the jury was whether or not it was murder or self defense, and Rose believed it was murder. In his outline to the jury, he pointed to Schumacher’s youth, weight and height, clear advantages over Scotty, and to the crushing blow on the side of McLachlan’s head that had broken his skull on both sides. In his opinion, it was a violent, purposeful attack.

To build his case, a number of experts were called to testify to McLachlan’s injuries. First was Dr. Lindsay. He described the post mortem examination he’d performed and verified that the body belonged to a man who was approximately 5’5” tall, between 45 and 60 years of age, with an old, healed ankle fracture. (Scotty was well known for having a limp from an old leg fracture.)

The skull was broken into twelve fragments on the left side. In addition, there were five fissures extending over the top and base of the head. Opening his travel bag, he brought out a small, cardboard box. Inside was the skull of Scotty McLachlan. He left the witness stand and went to the jurors, showing them at close range the various injuries to the skull. When he was done, he took the skull, including a piece from the base of the skull and all the little pieces of bone fragments and laid them all on a table, showing the jury what position they would have been in if the skull was whole. Next, he produced a normal skull, marked to show the breaks and fragments, with black spots indicating the pieces that hadn’t been recovered.

In Dr. Lindsay’s opinion, an extremely heavy blow on the left side of the head was the cause of all the breaks. He believed the blow had landed an inch and a half above and behind the left ear, which, from what he could tell, was the center of impact.

Outside of explosion wounds from shells during the war, he’d never seen a head so badly fractured.

During his cross-examination, Alfred Bence mimicked a position of attack. “A man striking this way would strike the person in the place you indicated?”

Dr. Lindsay agreed.

“One blow might have caused all the injuries, including the broken rib, if the joint of a fork, iron and handle caused the chief injury, the side of a fork could have broken the rib?”

It was a definite possibility, Dr. Lindsay agreed. Either way, he stated, the injuries were extreme and extreme force was clearly used.

Bence did his best to use this statement to his advantage, pointing out that while Schumacher was a powerful man, being in fear of his life would have lent him further strength.

Coroner Leckie of Lucky Lake testified next. He corroborated Dr. Lindsay’s testimony, stating that he’d never before seen a skull so badly fractured. He believed the force of the blow depended on the weight of the weapon and the wielder’s strength, admitting that the accused, a large man in terror of his life or serious injury, striking as hard as he could, could cause the injuries.

The final expert was Dr. Frances McGill, the Provincial Pathologist. She described the injuries to the skull and agreed with Dr. Lindsay’s testimony.

“It was a terrific blow.”

She’d not seen a worse broken head.

Rose continued to build his case, calling on Scotty’s friends and neighbours to testify. First up was Oscar Lindman.

He testified that the last time he saw McLachlan, there was no hint that he was planning to leave the district. And he would have known about it if he was. In fact, Scotty wanted Oscar to take him across the river the following Monday to get some money to fix up his harness and buy seed. He was going to sell some horses. And as far as Oscar knew, he hadn’t sold any of his horses or equipment to Schumacher.

Olaf Evjen was also called to once again tell the story of how he’d decided to terminate Scotty’s lease. He testified that he wasn’t getting anything back out of the farm. He was supplying seed and money for twine and “not getting nothing back.”

He talked to Schumacher about taking over the lease in the fall of 1927. He’d gone to Minnesota that November and while he was away he’d written Schumacher a letter that he would rent it to him in the spring when he came back. When he got back, he asked Schumacher where Scotty was. He was told Scotty left to go to BC.

In his opinion, Scotty drank quite freely.

Earnest Hagemeister was called to tell the story of the threat John had made. He told the court that about a month to six weeks before Scotty disappeared, he was sick in bed and Schumacher had come for a visit. They talked for a little while before Earnest finally asked him, “how are you getting along with Scotty? I was told he treated you with the frying pan?”

Schumacher told him, “I’ll kill that Scotchman yet.”

He believed that Schumacher was joking when he said it.

Jack Schultz, a clerk at Singer’s store, testified. He’d lived in the district for about two years and had lived with Schumacher on his farm for two months, from the beginning of November in 1929 until New Year’s.

One day he was helping Schumacher clean out the granary and they found a box with books and a few other odds and ends in it. They took it to the house to finish going through it. As they did, they found a set of false teeth in an Old Chum tobacco box. He asked whose they were and Schumacher said, “that is the pair Scotty left” and threw them in the stove.

He testified that sometimes at night before they went to bed, Schumacher made faces. He described it as a kind of grimace, his mouth pulling to one side. He couldn’t say if it was voluntary or not, just that he didn’t like it when Schumacher did it. Schumacher would also sometimes make noises in bed, tossing and turning enough to wake Jack up, although he never bothered to go and see what was the matter.

Jack Glazier, a farmer in Beechy, also testified. He knew Scotty pretty well, he’d stayed with him for a time when he first came to Beechy. He’d last seen Scotty sometime in January of 1928 at Oscar Lindman’s. He was staying there when Scotty came for a visit.

There was nothing to suggest during that visit that he was planning on leaving.

Jack was back at Oscar’s later that week when Schumacher came over. Schumacher told them the Scotchman had left the country. He clearly felt happy about it, he was jigging around, dancing a little.

Jack told the court that he didn’t think Scotty had been a hard drinker. He’d never seen him drunk, although he did drink on occasion.

Oscar Lindman’s wife, Hannah Lindman, confirmed that Schumacher was dancing about, happy, when he told them Scotty had left.

Peter Laplante and his sister, Isadore Laplante, both told the court that Schumacher had come over in the spring of 1928, wanting to take a team of Scotty’s horses. When Isadore asked him where Scotty was, he told her Scotty was in BC, in a hotel, sitting around, reading newspapers, smoking a big cigar and drawing his money.

Lizzie Nickerson, a widow from Beechy, testified that she kept house for Scotty from August 1926 until February 1927. She said the house was fairly well furnished and for a bachelor’s home it was all of pretty good quality; saying he had sterling silver cutlery. She gave the court a long list of the house’s contents and estimated the value at between $300-$500.

In the fall of 1927, she’d run into Schumacher at Beechy and asked him how he was getting along with Scotty. He told her that Scotty had held a frying pan over his head and that he was going to kill that Scotchman.

Constable Carey testified about the investigation and the arrest of Schumacher, telling the dramatic story of the confession and finding the body of Scotty McLachlan. At the telling of the confession, Schumacher’s wife became distraught, breaking down and having to be assisted from the courtroom.

Of course, Henry Gladstone, finally in good health, testified. He told the story of going to the farm and the confession, although according to him, Schumacher had cried, “I done it. I done it. I’ll tell it all.”

Alfred Bence had a simple strategy for the defense. Scotty McLachlan had attacked Schumacher and he’d killed him in self defense. He wanted to proved that Scotty was volatile, with a sometimes violent temper.

The first witness he called was a young, 20-year-old man named Wilson. He was a farmer at Beechy and had been to the McLachlan/Schumacher farm several times. In the spring of 1927, he’d been at a party at their place where there’d been a considerable amount of drinking. Scotty had gotten drunk and threatened him, eventually escalating to chasing him into another room with a butcher knife. At first, he’d thought Scotty was joking, but then realized he was serious. Scotty caught him and said something about performing an operation. He got away and Schumacher had come and taken Scotty away.

“Scotty wasn’t laughing,” he said, when on cross-examination Rose suggested it was all in jest.

Another witness was that of Mrs. Hatie Vohr, from Mission City in BC. She’d lived in Beechy but had left in 1927. She’d known Scotty since 1912 and had seen him in June of 1927 when he came to see about some horses he had in their pasture. He’d told her about his troubles, saying that he had “that good for nothing Schumacher” on his place. He decided to leave the horses until Schumacher left, telling her he would get rid of him if he had to kill him.

Earnest Hagemeister testified to a fight he’d had with Scotty in town at the hotel years earlier. It had been over a pig of some sort or another. Scotty was the first to get physical, despite Hagemeister being about 5’10” and around 280 pounds.

They scuffled, Hagemeister coming out on top. He stated that after the fight they were “all right”, with Scotty being “as friendly as he ever had been.” When asked, he said he wouldn’t describe Scotty as a clean fighter.

He’d also been at the home brew party where Scotty had chased Wilson with the butcher knife. He had already passed out before the row started but Schumacher had told him about it, saying that Wilson was badly frightened, although he’d still spent the rest of the night there.

Bence also called Schumacher’s older brother, Leslie, to the stand. He testified that John had been born in Wisconsin and didn’t get any schooling after Grade Four at the age of 13. The school was four miles from the farm and it didn’t seem worth it as he deemed his brother “kind of dumb.” John had come to Canada in 1921 and worked on farms in the Beechy district.

It was time to hear from the accused.

On the morning of March 25, 1931, with a bitterly cold east wind blowing ferociously outside, John Schumacher took the stand. He spoke in clear tones but was obviously nervous, his hands shaking as Bence had him verify the lease to the farm.

He admitted he never liked school. All he’d ever done was farm work.

In the spring of 1927 he’d rented a half section of land from McLachlan. The trouble between them had started soon after. Scotty had sent to Beechy for groceries in Schumacher’s name, leaving him with the bill. He tried to do it again on another occasion but Schumacher had already warned the storekeeper and he was turned down. They had a big argument over it, which was when Scotty threatened him with the frying pan.

There was fresh fuel for trouble when Scotty found out Schumacher had been offered the rental of the farm.

“He was pretty sore about it.”

Schumacher said the bad feelings lasted a few days and then they got along all right again. Scotty decided to sell out and leave the country. Schumacher bought some household goods and machinery, giving him a promissory note for $200 to be paid the next fall. He bought three horses from him, for which he paid $150 cash.

He told the court that Scotty died sometime in January of 1928. He was fairly certain it was in the morning. He saw Scotty coming up the road and was pretty sure they’d said good morning. He’d gone out to the barn and was cleaning the stalls, loading manure onto a stone boat with a four-prong manure fork.

Scotty came in and began swearing, calling Schumacher all kinds of names. He picked up a scoop shovel and swung it once, advancing on Schumacher. Schumacher had heard about fights involving Scotty, had heard Scotty himself boast about them. All this flashed through his mind as he swung the fork as hard as he could, knocking Scotty down.

He’d run to the house, then come back. He’d even jumped on a horse and rode over to Oscar Lindman’s, but no one was there so he rode back. He found himself thinking about the best way to get rid of the body, since he had no witnesses to the fight.

He dragged the body out of the barn, along a horse trail to the manure pile and covered it with straw and manure.

“Why did you conceal the body?” Bence asked.

“I was scared of the police. When I was a kid, I always heard they would hang a man for killing.”

He’d been afraid to go to his brother, afraid the body would be found. For three years he was afraid to leave and afraid to stay, haunted by the fear of discovery and the horror hidden beneath the manure and straw near the barn.

Terrified of being alone on the farm, he employed a succession of young men to keep him company until he married his wife.

Schumacher insisted that his confession on December 14, 1930 was the absolute truth. He killed in self defense.

John Schumacher’s wife went on the stand as well. She refuted Lizzie Nickerson’s claim about the nice furniture and sterling silver cutlery, saying it was a mixed, well-used lot, nothing fancy or valuable. She also claimed that it was she who burned Scotty McLachlan’s false teeth. They’d found them in a table drawer that had been brought in from the granary.

It was time for Alfred Bence to make his final argument. He told the jury that his client did not wish for a recommendation for mercy.

“All we want is justice.”

He reminded them that one could not judge a man’s character by his size; little dogs often had more courage than their much larger counterparts. Schumacher had a right to repel violence with violence, he was not obliged to run away, although he couldn’t have anyway. He was only 20 at the time, unaware of his own strength. An ignorant boy, who’d been told they hang people in Canada and made a fatal mistake when he hid the body instead of reporting it to the police.

Bence reminded the court that in Corporal Woods’ own testimony, he said “I was convinced that I got the true story from him. I was convinced he had a row with McLachlan and that he unluckily killed him during a fight.”

He’d suffered for three years because of this mistake and it had led to his predicament today. Concealing the body had led to lies about Scotty’s whereabouts and property, one falsehood inevitably leading to another.

Rose was not convinced. In his final argument he told the jury that there was no doubt Scotty had been killed. There was a tendency in sensational cases like these to forget the man who’d been struck down and sent to eternity in a moment. It was the Crown’s case that Schumacher was a murderer who’d done the deed deliberately from a motive of robbery.

He cited the numerous lies Schumacher told in the three years before the alleged crime was discovered. He didn’t believe that Schumacher had ridden to Oscar Lindman’s for help. And it was only because he had a horror of the body that he hadn’t take the watch from Scotty’s pocket. As for Woods’ testimony, he was not in possession of facts now known at the trial, pointing to the number of articles Schumacher had sold of Scotty’s.

It was time to leave the case with the jury. Justice Embury outlined the law, describing the difference between justifiable homicide and culpable homicide, the latter being divided into murder and manslaughter. He reminded them that a man comes into the court presumably innocent, and unless the crown has built a perfect wall of proof about him, he must be acquitted.

At 6:40 p.m., the jury was dismissed and taken to the old dining room of the hotel in town to begin their deliberations.

The next morning, on March 26, 1931, as Schumacher was being visited by his wife, baby and brother, the jury came up the street from the hotel. They’d reached a verdict. Schumacher, pale and nervous, scanned their faces as they filed in.

Bence was not present. He needed to leave for Wynyard for his next case and had caught a train to Saskatoon at 6:00 a.m. that morning. The decision, when announced, was wired to him.

John Schumacher was left alone to hear his fate. The jury found him guilty of manslaughter. It was 10:40 a.m.

Justice Embury remanded Schumacher until 2:00 p.m., when he imposed a sentence of seven years in the penitentiary. It was not the verdict Schumacher was hoping for, but it was much better than being found guilty of murder, which would have resulted in a sentence of hanging.

With the mystery finally solved, the community moved on. The skull of James “Scotty” McLachlan was kept as evidence and moved to the basement evidence vault in the Kerrobert Courthouse until it was interred with the rest of his remains in 1996 in Beechy.

Henry Gladstone moved away from Saskatoon, although he continued to offer to solve mysteries for the police and added “authority on criminology” to his bio. In 1939, as the world once again went to war, he predicted that it would last a long time and that Hitler and Mussolini would be killed at the hands of their own people.

Justice John Embury became the senior officer in charge of military registration and a chairman on the National War Services Board during the war until his sudden death in 1944.

John Schumacher was sent to the Prince Albert Penitentiary to serve his sentence. It’s unclear what happened to him after that. There’s some evidence that suggests that upon his release he moved back to the United States to escape his past. He certainly did not return to Beechy. His name did not appear in the newspapers again.