Leask, SK – July 27, 1935

Cecille Fouquette was in a bit of a jam. She was stranded at the YWCA in Saskatoon, unable to pay her bill, with her boyfriend held by police on several charges of theft. Unsure of what else to do, she called her dad and he agreed to help her.

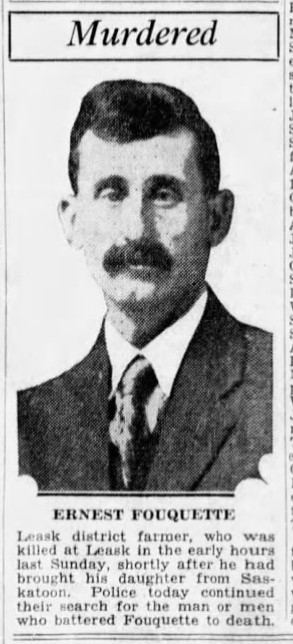

Ernest Fouquette, along with a friend, drove to Saskatoon and picked up his daughter, settled her bill at the YWCA, and paid the fines for her boyfriend, Leo Roy, so he could be released. Ernest then bought some beer and the group drove home to Leask, with Ernest riding as a passenger while he drank a few of the beer. At about 8:00 p.m. Ernest dropped off Cecille and her boyfriend at her mother’s small shack and continued on with his evening.

He and his hired man, Tony Verrault, drove to Marcelin, where they drank some beer at Joe Lecoursiere’s. According to Verrault, Ernest didn’t have enough money to pay for the drinks and a third man, Alphonse Renaud, paid the balance. They left Marcelin, arriving back in Leask at around 11:40 p.m. Ernest went to the Paris Cafe, and at around 12:30 a.m. he was seen leaving.

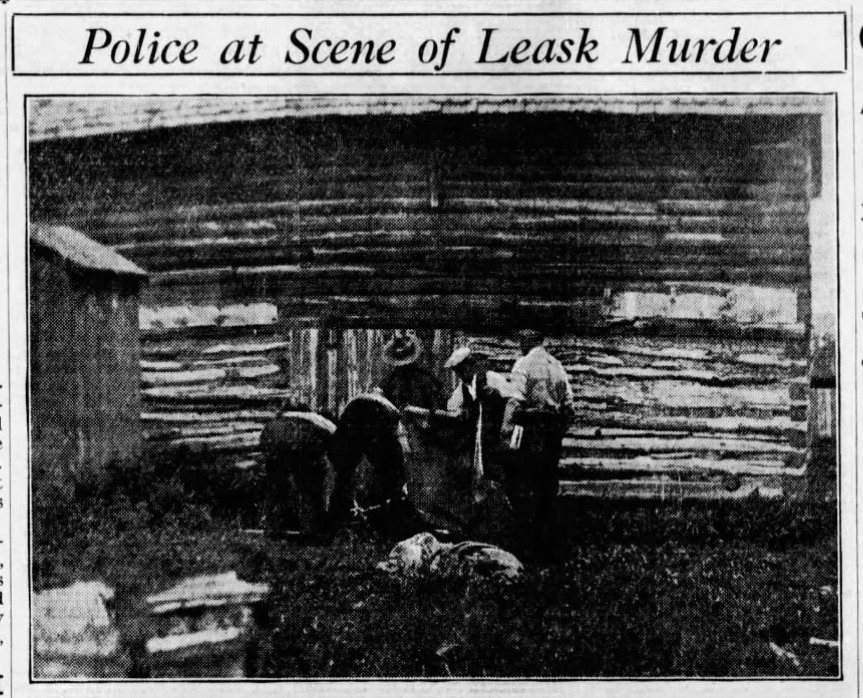

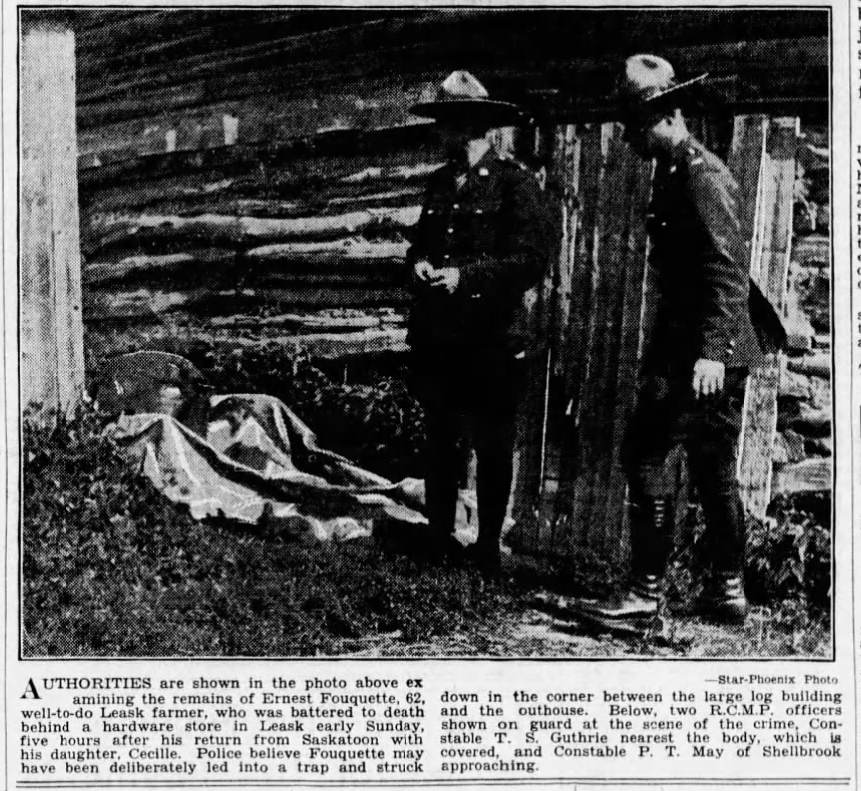

At about 1:30 a.m. the town constable, Lorne Jamieson, made his final rounds of the village. He’d been asked by Tony Verreault to keep an eye out for Ernest, as his hired men were waiting at the car to go home. In the alley behind Matthew’s Hardware Store, Constable Jamieson made a gruesome discovery. There in the grass was the battered remains of Ernest Fouquette, his face disfigured almost beyond recognition. He’d received multiple blows to the head, the brutality of which had knocked out pieces of bone and brain.

Constable Jamieson notified the RCMP and a doctor was called to the scene, who confirmed that Ernest Fouquette was dead.

For the small community of Leask, this violent murder was shocking. He was a well-to-do farmer in the area, with five quarter sections of choice land and a good reputation in the community. Although, that isn’t to say there weren’t plenty of people who didn’t like him.

Ernest had married his wife, Annie, in Radisson in 1914. He was about 40 at the time, she was only 16. They had nine children together before Annie obtained a judicial separation in October of 1934. She was awarded alimony of $60 per month for her and her children, but Ernest refused to pay.

That spring, when the court order for separation allowance was still not fulfilled, his chattels were seized and a sale was listed for March 18th. His friends, however, threatened to give any bidders “a ride on the tarred back of a dead steer… on a stone boat.” Needless to say, no one bid and the sale was called off. The court took no further action.

That same spring, Fouquette began to experience small bouts of trouble. Some wheat was stolen, horses were turned out of his pastures, and some articles were stolen from his car.

Aside from the bad blood between his ex-wife and her family, it was also well known that Fouquette had quarreled with a man named Nick Grovu, a relative of Annie’s by marriage, about three months before his murder.

An Inquest was opened on the afternoon of July 28th, and then immediately put on pause while the RCMP continued their investigation. It was slow going. Police interviewed Annie, as well as her brothers, Bill and Nick Lytwinic, and took a statement from Leo Roy. In October, they found an automobile spring in a slough about a quarter mile from town on the road to Fouquette’s farm that they believed might be the murder weapon.

When questioned about their progress, they told reporters; “It is a complete mystery and difficulty in getting those questioned to tell the truth is not helping much.”

The Inquest was finally resumed on November 4, 1935, partially because it took the RCMP that long to track down Nick Grovu, who’d sold out his farm chattels in the fall and moved to Saskatoon.

Witnesses at the inquest included Ernest’s eldest daughter, Cecille Roy, who’d married her boyfriend in August. She described her father coming to Saskatoon to pick her up, as well as getting home and finding her mother not at the shack. She and Leo both saw Nick Grovu stop by the shack at around midnight that night, looking for his wife. In regards to the separation, she told the court that her father had never given her mother a dime.

Dr. Frances McGill testified to the findings of her postmortem. She was of the opinion that Fouquette never moved a step following the first savage blow that cleaved his skull. His injuries included an inch long abrasion on the tip of his tongue, as well as a cut on the inner angle of the left side of his mouth that was about 3/8″ long. His upper eyelid was cut and his cheek showed bruises and several abrasions. His right eye was blackened and swollen, with a gaping cut above it about 3/4″ long and 1/2″ deep, cutting through the bone. Across his forehead was a 4 3/4″ wound that was 2″ wide and went straight through the bone, exposing bits of brain. On the left side of his head there was cut in his scalp extending about 1/2″, with a skull fracture beneath. There was yet another cut on the side of his head that was 3″ long, and both his nasal bone and his left jaw were fractured. To sum up, she told the jury, every bone in his skull showed multiple fractures, with the exception of his right cheekbone.

Death had been due to hemorrhage and extensive injuries to the brain. She believed that many blows must have been struck, and when asked about the auto spring the RCMP had located, she agreed it was possible it could have caused the wounds but she was doubtful about the big wound in the forehead. Notably, she also found some blood around some of his pockets, as though whoever killed him might have rifled through his clothes.

One by one, each of the key players in the RCMP’s investigation was asked to give a walk through of their movements on the evening of Fouquette’s murder.

Annie Fouquette had only just returned to Leask on the afternoon of July 27th, after visiting two of her daughters at Sandy Lake, followed by five days on the farm of her brother, Bill Lytwinic. She testified that she’d seen her daughter, Cecille, get back, but as she didn’t approve of the relationship with Leo Roy, she’d left and decided to walk to Bill’s with her daughters, Melvina and Delina, and her eldest son, Napolean. She testified that she had left town for the farm at least 45 minutes before Ernest was murdered. She also made some oblique references to her family’s suspicions that Ernest Fouquette may have been involved in a previous murder in the area, although I could find no articles about it in the newspaper archives.

Albert Nicholas was a hired man for Nick Grovu. He stated that he’d left town in Bill Lytwinic’s car at about 12:30 a.m. He recounted that at about 11:45 p.m. Bill had told him they’d be leaving soon, but then he’d disappeared. He waited around and talked with Tony Verrault and Siggur Larsen, who were sitting in Ernest Fouquette’s car, waiting for their boss. At about 12:15, Bill’s car drove down Main Street, and then about 10 minutes later it returned. He jumped on the running board, then got in the car. Nick Lytwinic was also in the car, as was Annie’s 8-year-old daughter, Jean. Before they could leave town, Nick got out of the car and went towards the police station. Albert lost sight of him, but he returned a few minutes later and the party then finally left town on the north road towards the Lytwinic farm. They met Annie and Malvena on the road and picked them up. He testified that the family spoke in Ukrainian, which he didn’t understand, and when they reached Hayward’s Corner, he, Malena and Jean were told to get out and the car went back to Leask. He walked to Nick Grovu’s, who was home at this point and gave him supper. He told the jury that Nick had later asked him to make a false statement, saying that he’d gotten home at 12:30, instead of at about 1:30/1:45 a.m.

Nick Grovu admitted that he didn’t like Ernest, but said he knew nothing of the man’s death. He denied that he’d visited Annie Fouquette’s shack around midnight that night, and denied the accusation that he’d asked his hired man, Albert Nicholas, to give an affidavit saying that he’d arrived back at Grovu’s at 12:30 that night.

Tony Verrault, hired man of Ernest Fouquette, stated that on the evening of July 27th he’d taken a radiator to a garage, then visited Marcelin with Ernest, where they drank some beer at Joe Lecoursiere’s. They’d left, arriving back at Leask at about 11:40 p.m. and Verrault had gone back to the garage to get his radiator, which he left in front of the garage to pick up later. He went back to Main Street, where he talked to two girls for about 10 minutes, then went into the cafe. Ernest was already there, as was the other hired man, Siggur Larsen, and Ernest’s son, Napolean. He said that Ernest had talked about his family on the trip back to Leask from Marcelin. He’d told him that Cecille was going to move back to the farm and he thought the other children would do the same. But Napolean didn’t seem to want to go home and refused to talk to him. “It’s funny when your own boy won’t talk to his dad,” he’d told Verrault.

After a short time, Verrault said that Ernest and Napolean had left together. He and Larsen left not long after and went to get the radiator. When passing the lane near where the body was found, they heard voices. When they returned, they went down the lane and saw what Verrault believed to be two men near a vacant tie-lot. He and Larsen, both carrying the radiator, continued up the alleyway and heard voices. Verrault was sure the voice belonged to Ernest, and that he said, “Nap, who does it belong to? Does it belong to your mother or me?” Next, he thought he heard Napolean answer, “Come here, I’ll speak to you,” or “Wait a minute, I’ll speak to you.”

They continued on to Fouquette’s car, where they waited, chatting with Albert Nicholas. He confirmed that he’d also seen Bill Lytwinic’s car drive down the street, then return. Next, they’d met the town constable and asked if he’d seen Ernest.

Siggur Larsen had much the same story. He’d seen Ernest in the Paris Cafe at about 11:40 p.m. as well as Napolean, Mrs. Grovu and Delina Fouquette. He saw Napolean leave, followed by Ernest. Later, when he was passing along the back lanes with Verrault, he heard who he believed to be Ernest say, “Who is the father of them kids? Who is to support them, your mother or me?” He hadn’t been able to make out the reply.

Towards the end of the inquest, Nick Grovu told detectives he’d like to add to his testimony. He pointed the finger at Napolean, declaring that his wife had been asked by one of the Fouquette girls to “provide an alibi for Napolean,” who was only 17-years-old. His wife, however, denied this statement.

Leo Roy volunteered a further statement, stating that he’d seen Mrs. Grovu attempting to burn some papers at her house after Nick Grovu was grilled by police following the murder. According to Roy, Grovu had threatened to “fix” his wife, and she’d been so terrified she’d left Leask for some time. He stated that Mrs. Grovu suspected her husband of the murder.

As for Napolean, he testified that he’d left Leask before the stores closed on July 27th. He stated that shortly after 11:00 p.m. outside of the OK Economy Store, his father had made him an offer, telling him he’d give Napolean the title to the farm at 21, if he came home. He’d told his father to put it in writing and then he’d consider it. He didn’t trust his father, but didn’t want to argue with him or discuss any farm deal unless it was on paper. He stated that he was never in the lane where his dad was murdered. The RCMP had noticed a cut on his knuckle in the days after the murder, but he stated that it was from working on his uncle’s tractor the day before the murder.

At the end of the inquest, the RCMP arrested Napolean Fouquette and charged him with the murder of his father. Throughout the inquest, Coroner R.L. King had admonished the witnesses for their continual avoidance of answering questions, often responding that they couldn’t remember. He asked the RCMP to arrest several witnesses for perjury, although it doesn’t appear that the threat was ever followed through.

On November 26, 1935, a preliminary hearing was held in Leask for Napolean Fouquette. He was represented by John G. Diefenbaker K.C., while G.M. Salter K.C. represented the Crown

The preliminary hearing went much the same as the inquest, although at this point Diefenbaker was able to cross examine some of the witnesses. In questioning Albert Nicholas, he got the man to admit that he’d only guessed at the time of events on the night in question. He didn’t wear a watch and had no way of knowing for sure what time any of it had happened.

As for the prosecution’s star witness, Tony Verrault, Diefenbaker uncovered a few interesting facts about him as well. It turned out that Verrault had once had an interest in Cecille, Ernest’s daughter. He had allegedly asked Ernest for a quarter section of land and some horses if he married her. Verrault denied this, as well as the assertion that he’d asked a priest about a marriage ceremony. Under more questioning, he admitted that he had indeed proposed marriage, “but had not been very serious.” He also denied rumors that he’d made threats to get even with “Napolean and the old woman” when his friendship with Napolean cooled after his mother separated from Ernest.

Napolean was committed to stand trial in February of 1936. It was then pushed back to April, while the Crown continued its investigations. The RCMP visited Saskatoon several time to question a woman related to Annie Fouquette, but it seemed their inquiries proved fruitless.

Finally, on April 28, 1936, Napolean was freed from jail, when a stay of proceedings was granted by Justice G.E. Taylor on request of the Crown prosecutor, G. M. Salter.

No one else was ever brought up on charges for the murder of Ernest Fouquette, and Napolean Fouquette never went on trial. With too many suspects and too little evidence, the question of who killed Ernest Fouquette remains unanswered to this day.

Information for this post was found in the following editions of the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix and the Regina Leader-Post: July 29, 1935, July 30, 1935, July 31, 1935, Aug 1, 1935, Oct 28, 1935, Nov 2, 1938, Nov 5, 1935, Nov 6, 1935, Nov 7, 1935, Nov 8, 1935, Nov 12, 1935, Nov 15, 1935, Nov 22, 1935, Nov 26, 1936, Nov 27, 1935, Nov 28, 1935, Nov 29, 1935, Nov 30, 1935, Jan 6, 1936, Jan 8, 1936, Feb 12, 1936, Feb 25, 1936, April 23, 1936, April 28, 1936, April 29, 1936

If you’d like to read more historical true crime stories from Saskatchewan, give these a try: